The Book:

SEABEE71

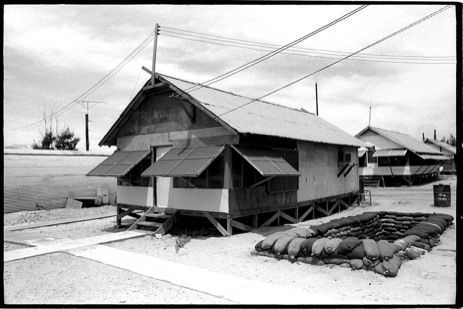

IN CHU LAI

A 350 page memoir of a Navy Journalist's 14 months with the Seabees.

Photographs and text copyright © 1967 and 2019 by David H. Lyman

All summer, I’d been watching Seabee builders create vertical projects—construction that went up. Teams from Alpha and Bravo Companies worked on horizontal projects, roads, runways, building foundations. As the men worked, they joked with and razzed each other.

“Hey! Spider Legs! Get that fat arse of yours over here. I need a hand with this siding,” shouts one ‘Bee to another.

“Keep your pecker in your pants, Fart face.” Comes the reply. Foul language is common in the Navy. I suppose it is in all the other services.

These jobs were routine to these men, something they could do in their sleep, while spinning yarns of conquests with high school cheer leaders, cars they’d rebuilt, bar fights, money made and lost. There was a lot of harmless name calling, as 2 x 4s, boards and sheets of plywood were cut, handed up and nailed in place. The Seabees got to put together things, real things, like metal Quonset Huts, stick built barracks. They laid down AM-2 aluminum slab matting to create a runway, mixed and poured concrete, laid down asphalt roads. They sweated, grunted, and laughed all day long. They got their hands dirty. They did physical things. At the end of the day they’d be exhausted, but they had the satisfaction of having built something.

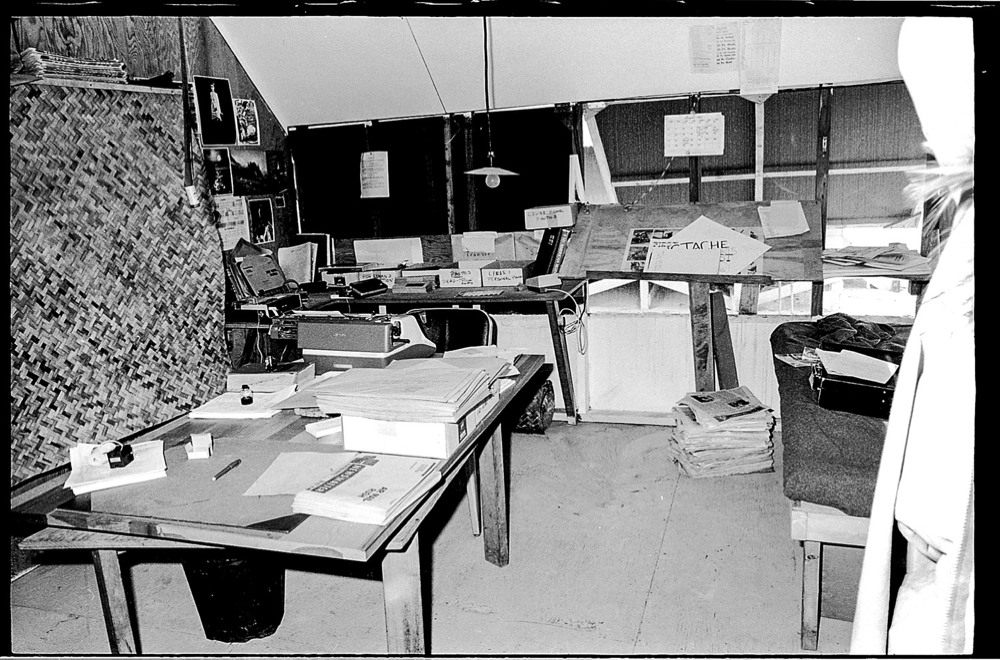

As a journalist, a photographer, I work pretty much alone. In the field, in the darkroom, at my manual typewriter. But I also got to put things together, just like then carpenters. Words and sentences built into paragraphs, which became complete stories, These, combined with photographs, headlines and captions formed pages of The Transit.

My work was more intellectual, less physical, but I too created something, something tangible that people read, laughed over and began to understand what it was like living and working ion the heat and dust of Vietnam with a war going on around us.

Journalists and photographers in 1967 worked with ancient technology. We used film and the darkroom to create images, a manual typewriter to create text. There was no delete key to correct a mis-typed letter, only a bottle of “white out,” or you rip out the page and begin all over again. Setting type was done at a letter press shop, in my case at the Stars and Stripes’ Unit Publication office in Tokyo. This involved Linotype machines that were a hundred years old, creating "slugs" with workds in molten lead. We used a pica rule to measure column widths. This was physical work, as we moved block of warm lead around on a metal topped counter, forming pages.

There was no Internet then, no Google or Wikipedia to help with research. Spell checking was done by looking up the word in Webster’s Dictionary. No Lightroom or Photoshop to tweak the contrast of a print, that was done in the field by under or over exposing film and compensating during development in the darkroom, then using various “grades” of paper to make a print. I could take hours of trial and error to arrive at a print that was acceptable.